CONTROVERSY

'It's complicated': Nasal spray or flu shot for pediatric vaccination?

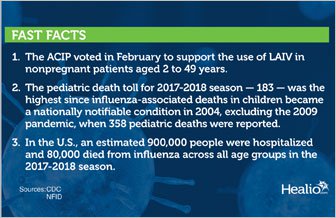

After recommending against the live-attenuated influenza vaccine, or LAIV, for 2 years in a row, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted in February to support its use in patients aged 2 to 49 years for the 2018-2019 influenza season. This was welcome news for physicians, parents and children alike because the vaccine, which is administered intranasally, is relatively painless.

However, the AAP’s Committee on Infectious Diseases (COID) recommended immunization with an inactivated influenza vaccine that is delivered intramuscularly as a first line of defense against illness in the current influenza season. The AAP did not fully endorse the quadrivalent LAIV FluMist (AstraZeneca), but said it can be used in certain pediatric populations who would not receive the influenza shot.

William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, said that the live-attenuated influenza vaccine - administered intranasally - is favored by parents, children and providers because it is painless compared with the intramuscular injection. However, national recommendations differ on the use of LAIV.

Both committees offered reasons for their recommendations after reviewing data on the nasal spray vaccine. Although their varying opinions on LAIV amount to a split decision, pediatric infectious disease specialists agree that what is most important is that children beginning at 6 months of age are vaccinated against influenza.

"It’s complicated. The effort has been to harmonize the recommendations between the AAP and the CDC," H. Cody Meissner, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Tufts University School of Medicine and an Infectious Diseases in Children Editorial Board member, said in an interview. "We all agree that the most important issue is that every child gets vaccinated. Every child 6 months or older should receive his or her annual influenza vaccine. And, if a child is between 6 months and less than 9 years of age, the child may need two doses of vaccine, depending on prior vaccination. That's the most important takeaway message that AAP and CDC want to transmit. Everyone should be immunized with an age-appropriate and health-status appropriate vaccine."

Infectious Diseases in Children spoke with specialists, including some who were active on the ACIP and AAP committees, to get a better understanding of why the two organizations arrived at different recommendations for this influenza season, and how pediatricians should integrate these recommendations into their practices.

A fork in the road

According to William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and medical director for the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, it was a matter of interpretation of available data that led the ACIP and AAP to make different recommendations about which vaccine providers should use this influenza season.

"There is a different emphasis of the use of LAIV by the two groups. Both organizations accept the use of LAIV," although the AAP has recommended LAIV not be used if there is an option to use the influenza shot, Schaffner told Infectious Diseases in Children.

The recommendation that the ACIP made in February followed a presentation of positive results from a U.S. study in children aged 2 to younger than 4 years that evaluated the shedding and antibody responses of the H1N1 strain in the quadrivalent LAIV. The study results demonstrated that the new 2017-2018 H1N1 post-pandemic strain (A/Slovenia) contained in the vaccine performed significantly better than the 2015-2016 H1N1 post-pandemic strain (A/Bolivia), which was previously associated with reduced vaccine effectiveness, according to an AstraZeneca spokesperson.

"The antibody response induced with the new H1N1 LAIV strain was comparable to earlier data seen with the highly effective H1N1 LAIV strain included in the vaccine before the 2009 influenza pandemic," the spokesperson told Infectious Diseases in Children. "The results of this study affirm that we successfully improved our strain selection process not only for the 2017-2018 season, but also for future seasons."

According to the CDC, the ACIP voted to make LAIV an option for vaccination once again after the root cause of its poor effectiveness against H1N1pdm09 viruses was uncovered and addressed by the manufacturer.

"There also were encouraging shedding and immunogenicity data suggesting that the problem may have been addressed," a CDC spokesperson told Infectious Diseases in Children.

The AAP took a more cautious approach for the 2018-2019 influenza season. Wendy Sue Swanson, MD, MBE, FAAP, a pediatrician at Seattle Children’s Hospital and a spokesperson for the AAP, said LAIV is expected to offer good protection against influenza, and acknowledged that the vaccine had been redesigned to address the ineffective strain, “but because of the lack of experience with success in children for that one strain, the AAP chose to preferentially recommend the shot this year."

"If your child will otherwise not get a flu shot (severe needle phobia) or if your pediatrician’s office doesn’t have supply, then getting the nasal flu spray is recommended,” she added.

Meissner, an ex officio member of the COID, expanded on the committee’s concerns.

Jose R. Romero

"AstraZeneca selected a new strain that is included in FluMist now," he said. "They have taken out the old H1N1 strain and included the new H1N1 strain. We don’t know if this new H1N1 strain will work in children. The company did demonstrate that this new strain replicated in the nasal mucosa and there is shedding, which is one alternative way of looking at how the vaccine works."

Meissner noted that although the ACIP felt there was sufficient evidence to reintroduce LAIV to the armamentarium, "the AAP said, 'Yes, that's good that the virus is shed, but how do you know it will protect against H1N1 disease?' So, the AAP has said we think it's good to have this vaccine. We need all the options we can use to protect against influenza, but we are not willing to say that it’s the equivalent to the killed vaccine at this time. How do you know that it will work as well against the H1N1 strain as the killed vaccine?"

Meissner said a concern of the committee is that in each influenza season, one viral strain predominates. For the 2017-2018 influenza season, that strain was H3N2, which usually causes more severe disease.

"We are due for a predominating H1N1 season," Meissner said. “What happens if the LAIV does not work against H1N1?"

He said the AAP would like to see additional data showing that the virus not only shed in nasal secretions in children who received LAIV but that vaccinated children who still developed influenza experienced less severe disease.

José R. Romero, MD, the section chief of pediatric infectious diseases at Arkansas Children’s Hospital and the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, chair of ACIP and an Infectious Diseases in Children Editorial Board member, said in an interview that the data presented by AstraZeneca before the ACIP’s decision “are as good as you can get."

"Short of carrying out true efficacy trials, that is how well the virus works in a real-world situation," Romero said. "The data presented to us were convincing to the vast majority, that the new vaccine may have addressed some of the problems of the previous vaccine. And because of that, the ACIP voted in the majority to reintroduce, or reconsider, this vaccine as an option for influenza vaccination in children."

Romero noted that his comments were his own opinion and that he was not making statements about ACIP or CDC policy.

Meissner calls the two organizations' recommendations "different, but similar," and that the disparity boils down to a difference in wording.

AAP says if a child refuses to get an intramuscular shot, it’s better that they get FluMist rather than no vaccine,” he said. “We all agree that the most important issue is that all children 6 months of age or older are immunized in an age-appropriate fashion."

Romero said the ultimate goal for pediatricians and pediatric infectious specialists is to improve the influenza vaccination coverage in children.

"Having a vaccine like LAIV that does not require an injection and generally is very child-friendly might improve the vaccine coverage among children," he said. “The problem this year is that we have basically a recommendation by ACIP for its use to providers and a very lukewarm recommendation by the AAP. So, that creates an atmosphere of uncertainty with the use of LAIV, at least for this year."

A high-severity season

Pediatric deaths related to influenza spiked in the 2017-2018 influenza season - a total of 183, according to the CDC, compared with 94 in the 2015-2016 influenza season and 110 in the 2016-2017 influenza season. The CDC noted that approximately 80% of pediatric deaths in the 2017-2018 influenza season occurred in children who had not received an influenza vaccination for the season.

The death toll for 2017-2018 was the second-highest since influenza-associated deaths in children became a national notifiable condition in 2004, trailing only the 2009 pandemic when 358 pediatric deaths were reported between April 2009 and October 2010, according to the CDC.

The 2017-2018 season was the first to be classified as “high severity” across all age groups. In the U.S., an estimated 900,000 people were hospitalized and 80,000 died from influenza, according to recent figures released at a news conference hosted by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

"Last year was an intense year... We had nasty viruses that were circulating. In general, when you have an H3N2 outbreak, you see high mortality rates in older adults," Pedro A. Piedra, MD, a professor of virology, microbiology and pediatrics and Baylor College of Medicine and an Infectious Diseases in ChildrenEditorial Board member, said in an interview.

He added that many of the pediatric deaths were related to influenza type B.

Wendy Sue Swanson

"Unfortunately, most of the children who die from flu are not vaccinated against flu,” Piedra said. "So the first thing one can say is: How can we improve influenza vaccine coverage in children and among the population as a whole? We know that vaccination is the best way to prevent influenza, even though it’s not a perfect vaccine. If you are not vaccinated, you are at greater risk for more severe complications from flu. And, while these numbers sound small, keep in mind that 50% of the children who die are perfectly healthy."

Not having LAIV available for children during the prior influenza season was not a major reason for the higher childhood death rate, Romero said. "I just think we had a bad season. You can never predict when it's going to be a bad influenza season. We were taken by surprise that we saw so much disease compared with previous years."

Limited supplies of LAIV

Piedra noted that by the time the ACIP and the AAP made their recommendations regarding LAIV, most medical facilities had already placed orders for influenza vaccines to prepare for the 2018-2019 season, and so relatively few stocks of LAIV were shipped in the U.S.

"Early winter is when ordering is performed by your major providers. It does not make for a perfect world for the LAIV," he said.

AstraZeneca told Infectious Diseases in Children that there are 2.7 million doses of LAIV available for the U.S. in the 2018-2019 season. The company said it began manufacturing quantities of LAIV for the 2018-2019 influenza season based on the initial demand estimates received from health care providers, which took place prior to the ACIP’s recommendation and the reopening of the Vaccines for Children program contract for supplemental orders of LAIV.

To put that in perspective, the CDC reported that as of Feb. 23, manufacturers shipped approximately 155.3 million doses of influenza vaccine - a record number — for the 2017-2018 influenza season. For the 2018-2019 influenza season, manufacturers projected having 163 to 168 million doses available in the United States, according to the CDC.

"There is a great deal of interest to see how much LAIV will be used in the U.S. during this season," Schaffner said. “Two years ago, it was a favorite of pediatricians and family doctors in the U.S. and a favorite of many children and their moms."

LAIV use elsewhere

Although LAIV was not recommended for children by the ACIP for two consecutive influenza seasons, it has been consistently recommended and used in Canada and Great Britain. In Great Britain, LAIV is the primary vaccine for children, Romero said.

Pedro A. Piedra

Following the ACIP’s reinstatement of LAIV, Public Health England published provisional end-of-season adjusted vaccine effectiveness estimates from the 2017-2018 influenza season. According to the AstraZeneca spokesperson, these results demonstrated that LAIV provided statistically significant vaccine effectiveness against A(H1N1) strains in children aged 2 to 17 years.

Meissner noted that until recently, the LAIV used in Canada was a trivalent formulation.

"You can't quite compare the immune response for the degree of protection between the vaccine in Canada and the vaccine in the United States, because they are not the same," he said.

Future use of LAIV in children

Schaffner said providers want as many options for immunizing their patients against influenza as possible. The more options, the more children.

However, the ACIP's previous decision to recommend against LAIV during a 2-year period did not appear to have a significant effect on vaccine uptake. Research published in Pediatrics showed overall child influenza immunization rates remained unchanged between the 2015-2016 and 2016-2017 influenza seasons.

Schaffner said it will take time to gauge how effective the reformulated LAIV is in children due to the limited supply available for the 2018-2019 influenza season.

"We anticipate that it will be difficult to make an assessment within the United States of how effective LAIV is going to be." Schaffner said. "We may have yet another season — the 2020 season - before we know how effective LAIV is. We will have data from Europe and Canada, but direct data from the U.S. will likely be postponed a year."

Romero agreed that it could be 1 to 2 years to determine whether parents and physicians will actually use LAIV.

"We do not know what is going to happen in the real world," he said.

(Source: Bruce Thiel In Infectious Diseases in Children, November 2018)

References:

- CDC. Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report.https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/#S3. Accessed October 18, 2018.

- Robison SG, et al.Pediatrics. 2017;doi:10.1542/peds.2017-0516.