Ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in India

How deadly is it likely to be?

March 23, 2020 12.15 AM

Last night I was listening to one of the many ongoing TV debates on the current COVID19 pandemic in India. One distinguished public health expert from the US predicted around 300 million cases in India based on certain mathematical models used in the western world. He went further and stated 200 million cases in the best-case scenario! These are huge numbers and probably he went overboard. No doubt, we have the 2nd largest population in the world and have a fragile health infrastructure, but even then, these statements may be viewed as creating panic and flaring unnecessary scare in the community.

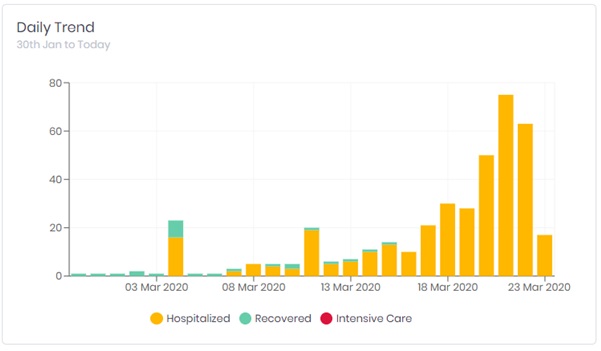

Undoubtedly, the current COVID19 outbreak is exceptional and truly unprecedented. The one attribute that separate COVID19 and other past pandemics is the speed with which it traversed and engulfed almost all countries of the Globe. No other pandemic be it 2003 SARS or 2009 H1N1 flu or the 2015 Zika had gripped the World as snugly as this outbreak. The whole world has come to a standstill. And India is no exception. As I write this piece, there are around 410 lab-confirmed cases with 8 deaths in India (Figure 2).

Most international health experts are puzzled looking on the Indian tally. They are not able to reconcile the fact that despite being the 2nd most populous country with proximity to China and with a jagged health infrastructure, India could manage to limit the spread of the disease so far. Even neighbour Pakistan has more than double the number of cases with daily escalation than India. It is now more than seven weeks since the first case of the outbreak was reported here. Many health professionals are forecasting India as the next big hotspot of the COVID 19 pandemic.

Then, what is the secret of Indian performance so far? What did India do differently than some other more developed nations could not do? Are the initiative and the pre-emptive steps taken by the government responsible for the current state? Or are these still the early days and the scenario would drastically change in coming weeks with the piling of ICU admissions and deaths? Or is it the sign of the waning of the pandemic? The answer to these queries is a big No. No doubt, the health ministry acted with some alacrity and launched a massive media blitzkrieg with highest political patronage involving the PM himself, and efficiently ensured isolation and quarantine of suspected people, but despite their best efforts some delay and ‘leakage’ of infected persons took place. Can anyone fathom an effective implementation of ‘social distancing’ in a street of Kolkata where shoulders are rubbed while walking during peak hours! Then, what key factor has kept the deadly virus at bay so far? And would prevent a déjà vu of the devastation witnessed in some other countries?

Saving Grace

The peculiar environmental/climatic conditions prevailing in India would act as a deterrent to the ‘swift’ transmission of SARS-CoV2. We have past experiences with many other viral outbreaks that could not do as much damage as they did in some other parts of the world. If one study the epidemiology of influenza virus, a respiratory virus with almost similar viral characteristics and route of transmission as the current coronavirus, it is apparent that Indian conditions are not conducive to its rapid diffusion in the population.

Let’s make a comparative analysis of the burden of annual influenza in the US and India. In 2017-18 season, there were an estimated 49 million cases of influenza-like illnesses, 960,000 hospitalizations and 79,000 deaths in the US whereas corresponding estimated figures for India were 16 million, 83 882, and 28, 000 despite having four-times more populous than the US!

One may argue that the current virus is far more transmissible than the flu virus, but if we analyse the ‘basic reproduction number’ or ‘Ro’ it is 2-2.5 for the SARS-CoV2 in China and other severely affected countries which is higher than seasonal flu (Ro: 1-2) but lower than SARS (Ro: 2-5) (Table 1). One should note that the ‘Ro’ is not a fixed entity, it varies considerably by the environmental conditions, population density and profile of the vulnerable population. Consequently, the SARS-CoV2 may be having a different Ro in India than in Europe or some other countries.

Table 1. Values of Ro and route of transmission of well-known infectious diseases

| Disease | Route of Transmission | Basic reproduction number (Ro) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measles | Airborne droplet | 12-18 | |

| Diphtheria | Saliva | 6-7 | |

| Smallpox | Airborne droplet | 5-7 | |

| Polio | Feco-oral | 5-7 | |

| Rubella | Airborne droplet | 5-7 | |

| Mumps | Airborne droplet | 4-7 | |

| Pertussis | Airborne droplet | 5-6 | |

| HIV/AIDS | Sexual contact | 2-5 | |

| SARS (2003-04) | Airborne droplet | 2-5 | |

| Influenza | Airborne droplet | 1-2 | |

| Ebola | Bodily fluids | 1.5-2.5 | |

| MERS-CoV (Saudi Arabia & South Korea) | ?Close contact/ ?respiratory secretions | 0.6-0.7 & 2-5 (nosocomial) | |

| SARS-CoV2 | Respiratory droplets | 2-2.5 |

Take the case of another respiratory virus, the measle, which is one of the most contagious viral infection. For measles, the ‘Ro’ is often cited to be 12-18, which means that each person with measles would, on average, infect 12-18 other people in a totally susceptible population. India had great difficulty in containing measles despite running a large, mass vaccination program for over 35 years. The very high virulence of measles virus was responsible for the intense transmission of the virus in Indian conditions. The SARS-CoV2 is not as lethal as the measles virus is. Even its virulence is far less than the other pandemic viruses like SARS or Ebola virus.

In the current pandemic, the northern parts of both Italy and Iran are more severely affected than other regions that have comparatively more sunny days (Figure 3). Do ultraviolet rays, abundant in sunrays, offer some sort of resistance to the viral transmission? Similarly, the hot, tropical environment in India would have an adverse effect on viral transmission and shedding. In a recently published paper from China, it is noticed that high temperature and high relative humidity significantly reduce the transmission of COVID-19. The authors conclude that one-degree Celsius increase in temperature and 1% increase in relative humidity lower Ro by 0.0383 and 0.0224, respectively. Similar findings were observed when influenza transmission was studied in tropical countries. The epidemiology of the current pandemic also reflects relative sparing of nations having tropical weather such as most countries in Africa and South America. We may be having a low ‘Ro’ of the currently circulating SARS-CoV2 than in most countries having temperate conditions.

People may argue that the one key difference between seasonal flu and SARS-CoV2 is the zero immunity against the latter since it is a newly introduced virus. But we have a similar experience with swine-flu aka H1N1 flu pandemic in 2009-2010 which was not proved as devastating as feared by the most. That pandemic resulted in total 10,193 cases with 1,035 deaths after one year. Considering the extraordinary, unprecedented steps taken by the government this time may further limit the damage.

In India just like many other tropical countries, the preferred route of transmission is feco-oral than the respiratory. Consequently, there is a preponderance of water-borne illnesses than those transmitted by air. Polio transmission exemplifies this phenomenon quite well. While in the tropical countries, the preferred route of transmission is through ‘feco-oral’ rather than ‘oro-oral’ or pharyngeal route which is the norm in countries with a temperate climate. Thus, a single disease is transmitted differently in different environs. All these factors shall provide hindrances to the smooth transmission of SARS CoV2 and should limit its spread in India.

How deadly is SARS CoV2?

As per the global data, 13,234 fatalities are reported out of 312,766 total positive cases giving a fatality rate of 4.2%. India, which has strategized to do limited testing until recently, also have around 2% fatality rate. But these figures are quite misleading and do not reflect the true virulence of the virus. As we all know, there is marked variability in the testing strategy of different countries and most countries barring few (like South Korea) have tested only severe cases or those with history of travel to infected countries. Since as many as 30-40% infections may be asymptomatic or having very mild disease, the denominator seems imperfect. Hence, we do not know the exact number of total SARS-CoV-2 infections. In only one instance, the outbreak on Diamond Princess cruise ship in Japan, the death rate was calculated with some precision which came around 1%. But even this might have been an over-estimation since most of the passengers on the ship were elderly people, and some experts have suggested a much lower estimate for the general population that is not much different from seasonal flu.

In the worst-case scenario, the national tally should not go beyond H1N1- pdm2009 (Swine flu) tally with a thousand deaths!

The future projections

So, what would be the ultimate course of the current pandemic in India? How many cases and deaths would occur? It is the most difficult query to answer considering these are still early days. But one thing that can be most certainly predicted- it would not go the way it went in Italy or Spain. The reasons enumerated above, and the pattern of the outbreak so far gives us some assurance. Most of the past flu outbreaks in last five years in India have confined to the first 3-4 months, i.e. till March-April. We are already in the 7th week of the outbreak and yet to encounter the huge multiplications of the cases. Neither there is the rapid filling of ICUs with the elderly population. Without resorting to any mathematical modelling and based on past-experience, it can be safely stated that in the worst-case scenario would be repeating the swine-flu tally with a thousand deaths. Those public health experts who are predicting doom for India with 2-3 million deaths are probably not aware of the particular environmental conditions and the course of some recent past pandemics in India.

--Dr Vipin M. Vashishtha, MD, FIAP. Director & Consultant Pediatrician, Mangla Hospital & Research Center, Bijnor-246 701 (Uttar Pradesh), India.